Blog > October In the Yellow Dog Watershed

October In the Yellow Dog Watershed

By Rochelle Dale

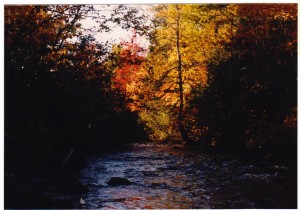

Octobers on the Yellow Dog always remind me of Aunt Mildred and my mom and dad. They would have been in their seventies at the time, back in the early 1990s. We were driving along the Toboggan road that runs parallel with the river when Mildred pointed out a young spruce tree covered in the yellows and reds of fallen maple leaves. She said, “Why, that’s as pretty as any Christmas tree I ever did see. “

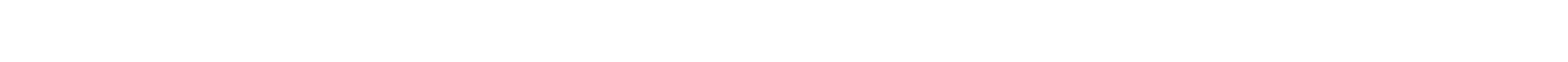

They were central Indiana farmers who no longer had large forests as we do here, so we stopped to admire and talk about the elegant simplicity of these natural decorations. The next October, I took a photograph of the river bends with the trees in full color along the shores, and I sent a framed copy to her that she kept on top of her T.V. until she died.

Mildred and both of my parents are gone now, like this year’s leaves. October marks the passing of another summer, the change from summer to winter. It makes me think about change, its inevitability or its absence, its forward progress or its backward consumption. Some changes, like the falling leaves, are expected and natural, as is my transformation from young mother to grandmother, from young adult to elder. On the other hand, those unnatural changes, the ones that often hide behind other words such as technological advancement, the way of the future, or progress, worry me.

In 2010, a gravel pit opened across the Yellow Dog River from my home. It was supplying crushed rocks for the construction of the Eagle Mine facilities, and they worked from sunup till sundown, 6:00 a.m. to 10:00 p.m., week-ends included. Because of the way sound travels, the rock crusher sounded as if it were in my front yard. Instead, it seeped into my being, and I started to feel like that machine. On further investigation, several concerned residents discovered that in the uphill approach to the gravel pit, two creek crossings were damaged and threatened with sediment and other debris. Soon this same group of citizens, including myself, attended the appropriate township board meeting to express our concerns about possible environmental degradation and to inquire about the required permits for this kind of operation. The gravel pit, we were told, did not need a permit because it was allegedly grandfathered in. Then, in the end, board members indifferently dismissed our complaints and environmental concerns with, “ This is progress. Get over it. “

When the Eagle Mine project first came to this area and they aimed to sway public opinion, they told Big Bay residents that their impact would be small, that we would hardly notice them. Now, they have spread like an especially aggressive invasive plant species. From Marquette to county road 510, road workers swarm the soon to be highway, erecting new bridges, digging deeper ditches, cutting trees, paving and repaving. Once rustic 510 to the AA A is now a 55 mph blacktop with shiny silver guard rails adorning the sides. The AAA is paved as well. The entrance to pinnacle falls is shrouded by a trucker’s depot. No trespassing signs litter the drives where we once followed the trails to potential warbler habitat or blueberry fields. And I wonder, is this the progress the board members meant?

I am reminded of a passage in Imagination and Place by Wendell Berry:

. . .nothing now exists that is so valuable as whatever theoretically might replace it. Every place must anticipate the approach of the bulldozer. No place is free of the threat implied in such phrases as “economic growth,” “ job creation,” “ natural resources,” “human capital,” “bringing in industry,” even “bringing in culture”—as if every place is adequately identified as “the environment” and its people as readily replaceable parts of a machine. Devotion to any particular place now carries always the implication of heartbreak. (21)

I understand the kind of heartbreak that Berry describes. I know what these changes and this progress in our rural neighborhood mean to me now, but I can’t predict what they will mean to my new granddaughter. What will the paved roads bring with them? What will be the effect of the hustling mine on the plains? Already the spirit of the place is hurting, and I worry because I dream that Florence and my grandchildren yet to come will find beauty here, will love this land as I do, will be devoted to this place. I want them to marvel at nature’s ways, as Mildred and my parents did twenty-five years ago on a sunny afternoon in October.